Enhance your health with free online physiotherapy exercise lessons and videos about various disease and health condition

SCI Rehabilitation

SCI Rehabilitation guide most persons with SCI to carry out meaningful work, and that the objective “return to work or school” is thus desirable and realistic in most cases.

Several factors contribute to poor overall physical fitness among persons with SCI. Paralysis by itself limits mobility and therefore the potential for exercising. Psychological factors such as depression decrease motivation to exercise. These factors contribute to increase risk for cardiovascular disease, hypertension, insulin resistance, musculoskeletal complications and obesity.

High-level SCI, in particular, leads to patho-physiological cardiovascular changes that further limit aerobic capacity. Moreover, paralyzed muscles atrophy to a greater or lesser extent, which contributes to an unfavorable body composition, insulin resistance, and associated adverse conditions. For many reasons, patients with SCI should become more physically active and thus need SCI rehabilitation.

Spinal Cord Injury Introduction

Spinal cord injury is not a notifiable disease and therefore figures for the annual incidence are inaccurate and may vary according to the source. The estimated incidence of spinal cord injury worldwide is between 11 and 53 cases per million inhabitants (Tator 2004).

In general, road traffic accidents account for the largest number followed by falls, sports injuries and violence, although causes vary considerably according to the prevailing circumstances in the country in which they occur. The numbers are augmented by the group of people with spinal cord damage caused by disease or other forms of injury, e.g. stab wounds.

Until Sir Ludwig Guttmann pioneered a positive approach to the treatment of spinal cord lesions at Stoke Mandeville Hospital in the mid-1940s, most people died of the resultant complications (Guttmann 1946). Regrettably this can still happen today where appropriate skills, knowledge and facilities are not readily available. Spinal injury units now exist worldwide and international symposia on the treatment of those with spinal cord lesions take place regularly.

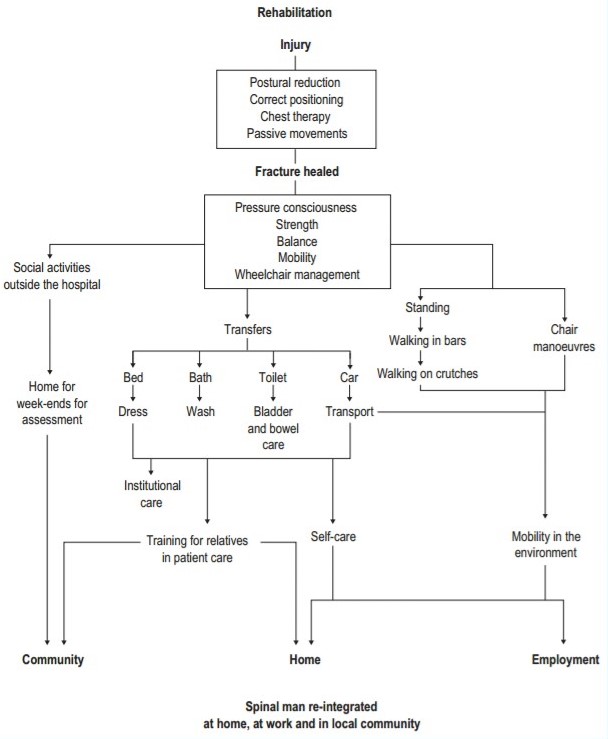

The life expectancy of this group of people has steadily increased over the last six decades, and with constantly improving methods of treatment and SCI Rehabilitation this trend should continue. Patients with spinal cord injury are initially totally dependent on those around them and need expert care if they are once again to become independent members of the community. It is an exciting and rewarding challenge to be involved in and contribute to the metamorphosis which occurs when a tetraplegic or paraplegic patient evolves into a spinal man.

Solutions to the majority of problems facing those with paraplegia have now been found, whereas many of the social, professional and industrial rehabilitation problems of those with tetraplegia have still to be solved. The tetraplegic patient needs a longer period of SCI rehabilitation to achieve maximum independence and overcome the sometimes apparently insurmountable obstacles.

The majority of the traumatic cases are found to have fractures/ dislocations, fewer than a quarter have fractures only, and a very small number are found to have involvement of the spinal cord with no obvious bony damage to the vertebral column, e.g. those with whiplash injuries. The most vulnerable areas of the vertebral column would appear to be:

● lower cervical, C5–C7

● mid-thoracic, T4–T7

● thoracolumbar, T10–L2.

The non-traumatic cases are mainly the result of transverse myelitis, tumours and vascular accidents. Thrombosis or haemorrhage of the anterior vertebral artery causes ischaemia of the cord with resulting paralysis.

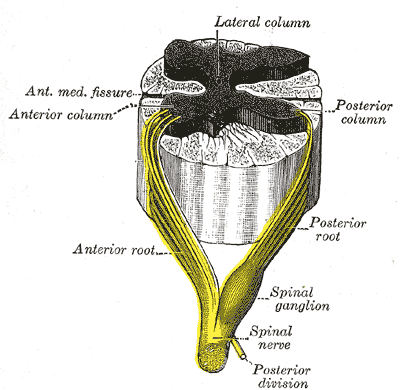

Spinal cord damage resulting from either injury or disease may produce tetraplegia or paraplegia depending upon the level at which the damage has occurred, and the lesion may be complete or incomplete.

Tetraplegia

This term refers to impairment or loss of motor and/ or sensory function in the cervical segments of the spinal cord due to damage of neural elements within the spinal canal. Tetraplegia results in impairment of function in the arms as well as in the trunk, legs and pelvic organs. It does not include brachial plexus lesions or injury to peripheral nerves outside the neural canal.

Paraplegia

This term refers to impairment or loss of motor and/or sensory function in the thoracic, lumbar or sacral (but not cervical) segments of the spinal cord, secondary to damage of neural elements within the spinal canal. With paraplegia, arm function is spared, but depending on the level of injury, the trunk, legs and pelvic organs may be involved. The term is used in referring to cauda equina and conus medullaris injuries, but not to lumbosacral plexus lesions or injury to peripheral nerves outside the neural canal. (Ditunno et al 1994)

LEVEL OF LESION

There are 30 segments in the spinal cord: 8 cervical, 12 thoracic, 5 lumbar and 5 sacral. As the spinal cord terminates between the first and second lumbar vertebrae, there is a progressive discrepancy between spinal cord segments and vertebral body levels.

MEASUREMENT SCALES

The International Standards for Neurological and Functional Classification of Spinal Cord Injury were published in 1994 (Ditunno et al 1994). These standards provide a tool to determine neurological level and to calculate a motor, sensory and functional score for each patient. They represent a valid, precise and reliable minimum data set. The neurological levels are determined by examination of the following:

● a key sensory point within 28 dermatomes on each side of the body

● a key muscle within each of 10 myotomes on each side of the body. The sensation and motor power present are quantified, giving a final numerical score.

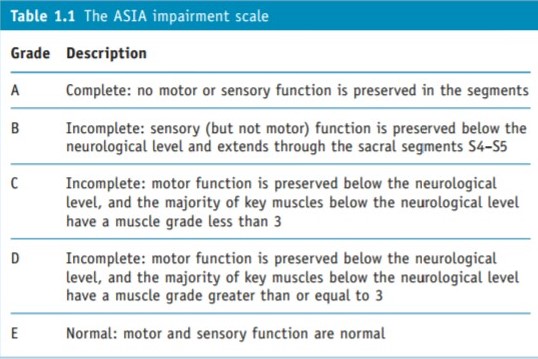

This is achieved by using the spinal cord injury scale of the American Spinal Injury Association (the ASIA scale) to grade impairment of sensation and motor power, and the Functional Independence Measure (FIM) to measure disability and grade function.

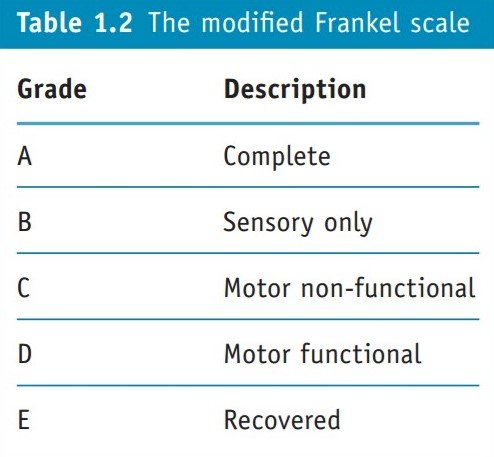

The ASIA impairment scale is based on the Frankel scale (Capaul et al 1994). The letters A to E are used to denote degrees of impairment. The Frankel scale has broader bands than the ASIA scale, so unless there is marked improvement or deterioration it is more difficult to show change.

The FIM, as its name states, is devised to measure function for any disability. Each area of function is evaluated in terms of independence using a seven-point scale. A total score from all these measures is calculated each time an assessment is carried out and progress can be readily seen.

Clinicians are using the ASIA scale and reporting that its accuracy is greater than the Frankel scale in classifying injuries and monitoring progress (Capaul et al 1994, Tetsuo et al 1996). Others suggested amendments (El Masry et al 1996).

The Spinal Cord Independence Measure (SCIM) (Catz et al 1997) was developed to provide a more sensitive measure than the FIM scale for assessing changes in function (Catz et al 2001a). The SCIM covers self-care, respiratory and sphincter management and mobility. A revised version, SCIM II, combines the scores on the ASIA and the SCIM scales (Catz et al 2001b). Catz et al (2004) have developed the Spinal Cord Injury–Ability Realization Measurement Index (SCI-ARMI). The difference between the expected and actual function achieved is used to predict and assess the success of the SCI rehabilitation programme.

Measuring the success of SCI rehabilitation is extremely difficult. The Needs Assessment Checklist (NAC) has been developed to measure the outcome of ScI rehabilitation and takes a much wider view of what is required than the other scales (Kennedy & Hamilton 1999). The outcome of the patient’s rehabilitation is assessed on the goals the patient and the multidisciplinary team have set together. It is completed when the patient is first up in the wheelchair and again prior to discharge.

Indicators have been set in nine areas: activities of daily living, skin management, bladder management, bowel management, mobility, wheelchair and equipment, community preparation, discharge coordination and psychological issues.

In addition to these measures, some therapists and other professionals are using the Ashworth scale of muscle spasticity.

Therapists now have tools to measure the outcome of SCI rehabilitation and to identify landmarks in the recovery of patients with spinal cord lesions.

SCI rehabilitation Include

Exercise

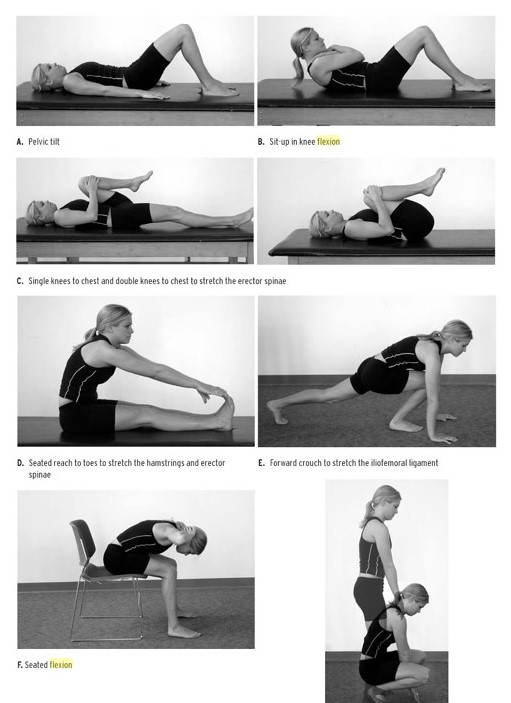

Arm cycling is a good exercise option for many patients, especially to achieve cardiovascular fitness. Since arm strength is also important for most patients with paraplegia and low tetraplegia, regular strength training should be added to the program. A modified version of circuit training, in which the patient goes from one strength training station to the next without pausing, has proven to be particularly effective since it combines strength and cardiovascular training. To prevent muscular imbalance, the focus is mainly on strengthening the upper back and shoulder muscles, as well as on stretching the pectorals. The strength training and cardiovascular exercise programs for SCI patients should be designed in cooperation with qualified healthcare personnel and be combined with other health-promoting initiatives, including diet modification, smoking cessation, and moderating alcohol consumption to achieve optimal results.

SCI Related Pages

Functional electrical stimulation

Functional electrical stimulation (FES) has been used mainly in the United States as a mode of exercise. Through electrical impulses, FES stimulates paralyzed muscles to contract, which exercises them. Electrically induced muscle activity leads to increased muscle mass as long as the stimulation program continues. If electrical stimulation is used for leg cycling, especially combined with “regular” arm cycling, cardiovascular benefit can also be achieved. This approach has demonstrated regression of left ventricular atrophy and, thus, improved aerobic capacity improved lower extremity circulation, improved body composition with more muscle and less fat, decreased insulin resistance and, according to some studies, some degree of anti osteoporosis effect. Naturally, such benefits presume continued, regular exercise, which is time consuming in part due to placement of electrodes on the lower extremities. Furthermore, FES bicycles are expensive, and the exercise method has not gained a significant foothold outside the U.S.

Sports in SCI Rehabilitation

The father of modern SCI care, Ludwig Guttmann, emphasized early on the importance of sports in the SCI rehabilitation process because of its therapeutic value for physical, psychological, and social reasons. Many national and international centers for SCI rehabilitation have designated recreational therapists (RTs) and/or rehabilitation instructors. There is significant overlap and a blurred distinction between their work on the one hand and that of physical therapists, occupational therapists, and social workers. A variety of hobbies, leisure activities, sports, and athletic pursuits are available with or without major or minor adaptations. Some of the activities shown to be particularly appealing to persons with SCI include horseback riding, archery, wheelchair basketball, quadrugby (wheelchair rugby for people with tetraplegia), wheelchair tennis, kayaking, wheelchair marathons, and sailing. In the context of sports for people with disabilities, athletes are classified according to their neurological and functional status. The purpose is to achieve the fairest grounds for competition possible by defining persons with comparable degrees of disability.

References for SCI Rehabilitation

- Tator C H 2004 Current primary to tertiary prevention of spinal cord injury. Topics in Spinal Cord Injury Rehabilitation 10(1):1–14

- Guttmann L 1946 Rehabilitation after injury to spinal cord and caudal equina. British Journal of Physical Medicine 9:130–160

- Ditunno J F, Young W, Donovan W H, Creasey G 1994 The international standards booklet for neurological and functional classification of spinal cord injury. American Spinal Injury Association. Paraplegia 32:70–80

- Capaul M, Zollinger H, Satz N et al 1994 Analyses of 94 consecutive spinal cord injury patients, using ASIA definition and modified Frankel score classification. Paraplegia 32:583–587

- El Masry W S, Tsubo M, Katoh M et al 1996 Validation of the American Spinal Injury Association (ASIA) Motor Score and the National Acute Spinal Cord Injury Study (NASCIS) Motor Score. Spine 21(5):614–619

- Catz A, Itzkovich M, Agranov E et al 1997 SCIM – Spinal Cord Independence Measure: a new disability scale for patients with spinal cord lesions. Spinal Cord 35:850–856

- Catz A, Itzkovich M, Agranov E et al 2001a The Spinal Cord Independence Measure (SCIM): sensitivity to functional changes in subgroups of spinal cord lesion patients. Spinal Cord 39:97–100

- Catz A, Itzkovich M, Steinberg F 2001b The Catz–Itzkovich SCIM: a revision of the SCIM. Disability and Rehabilitation 23:263–268

- Kennedy P, Hamilton L R 1999 The Needs Assessment Checklist: a clinical approach to measuring outcome. Spinal Cord 37:136–139

- Rehabilitation of Persons With Spinal Cord Injuries medscape.com

Return from SCI Rehabilitation to Home page

Recent Articles

|

Author's Pick

Rating: 4.4 Votes: 252 |