Enhance your health with free online physiotherapy exercise lessons and videos about various disease and health condition

Lumbar Spondylosis

Lumbar Spondylosis is a condition associated with degenerative changes in the intervertebral discs and facet joints. Spondylosis, also known as spinal osteoarthritis, can affect the lumbar, thoracic, and/or the cervical regions of the spine. Although aging is the primary cause, the location and rate of degeneration is individual. As the lumbar discs and associated ligaments undergo aging, the disc spaces frequently narrow. Thickening of the ligaments that surround the disc and those that surround the facet joints develops. These ligamentous thickening may eventually become calcified. Compromise of the spinal canal or of the openings through which the spinal nerves leave the spinal canal can occur.

Spondylosis often affects the lumbar spine in people over the age of 40. Pain and morning stiffness are common complaints. Usually multiple levels are involved (eg, more than one vertebrae). The lumbar spine carries most of the body's weight. Therefore, when degenerative forces compromise its structural integrity, symptoms including pain may accompany activity. Movement stimulates pain fibers in the annulus fibrosus and facet joints. Sitting for prolonged periods of time may cause pain and other symptoms due to pressure on the lumbar vertebrae. Repetitive movements such as lifting and bending (eg, manual labor) may increase pain.

Spondylosis Definition

SPONDYLO is a Greek word meaning vertebra. Spondylosis generally mean changes in the vertebral joint characterized by increasing degeneration of the intervertebral disc with subsequent changes in the bones and soft tissues. Disc degeneration, spinal canal stenosis, spondylolisthesis are the resultant pathological changes.

Lumbar spondylosis encompasses lumbar disc bulges, herniations, facet joint degeneration, and vertebral bony overgrowths (osteophytes). Degenerative changes, including osteophyte formation, increase with age but are often asymptomatic. Disc herniation is symptomatic when it causes nerve root compression and spinal stenosis. Common symptoms include low back pain, sciatica, and restriction in back movement. Treatment is usually conservative, although surgery is indicated for spinal cord compression or intractable pain. Relapse is common, with patients experiencing episodic back pain.

What Causes Lumbar Spondylosis?

Spondylosis is mainly caused by ageing. As people age, certain biological and chemical changes cause tissues throughout the body to degenerate. In the spine, the vertebrae (spinal bones) and intervertebral discs degenerate with ageing. the intervertebral discs are cushion like structures that act as shock absorbers between the vertebral bones.

One of the structures that form the discs is known as the annulus fibrosus. The annulus fibrosus is made up of the 60 or more tough circular bands of collagen fiber (called lamellae). Collagen is a type of inelastic fiber. Collagen fibers, along with water and proteoglycans (types of large molecules made of a protein and at least one carbohydrate chain) help to form the soft, gel-like center part of each disk. This soft, center part is known as the nucleus pulposus and is surrounded by the annulus fibrosus.

Risk factors for developing lumbar spondylosis

• Age: As a person ages the healing ability of the body decreases and developing arthritis at that time can make the disease progress much faster. Persons over 40 years of age are more prone to developing lumbar spondylosis.

• Obesity: Overweight puts excess load on the joints as the lumbar region carries most of the body’s weight, making a person prone to lumbar spondylosis.

• Sitting for prolonged periods: Sitting in one position for prolonged time which puts pressure on the lumbar vertebrae.

• Prior injury: Trauma makes a person more susceptible to developing lumbar spondylosis.

• Heredity or Family history

Pathology

The degenerative effects of ageing can cause the fibers of the discs to weaken, causing wear and tear. Constant wear and tear and injury to the joints of the vertebrae causes inflammation in the joints. Degeneration of the discs leads to the formation of mineral deposits within the discs. The water content of the center of the disc decreases with age and as a result the discs become hard, stiff, and decreased in size. This, in turn, results in strain on all the surrounding joints and tissues, causing the sensation of stiffness. With less water in the center of the discs, they have decreased shock absorbing qualities. An increased risk of disc herniation also results, which is when the disc abnormally protrudes from its normal position.

Each vertebral body contains four joints that act as hinges. These hinges are known as facet joints or zygapophyseal joints. The job of the facet joins is to allow the spinal column to flex, extend, and rotate. The bones of the facet joints are covered with cartilage (a type of flexible tissue) known as end plates. The job of the end plates is to attach the disks to the vertebrae and to supply nutrients to the disc. When the facet joints degenerate, the size of the end plates can decrease and stiffen. Movement can stimulate pain fibers in the facet joints and annulus fibrosus. Furthermore, the vertebral bone underneath the end plates can become thick and hard.

Degenerative disease can cause ligaments to lose their strength. A ligament is a tough band of tissue that attaches to joint bones. In the spine, ligaments connect spinal structures such as vertebrae and prevent them from moving too much. In degenerative spondylosis, one of the main ligaments (known as the ligamentum flavum) can thicken or buckle, making it weaken.

Knobby, abnormal bone growths (known as bone spurs or osteophytes) can form in the vertebrae. These changes can also cause osteoarthritis. Osteoarthritis is a disease of the joints that is made worse by stress. In more severe cases, these bones spurs can compress nerves coming out of the spinal cord and/or decreased blood supply to the vertebrae. Areas of the body supplied by these nerves may become painful or develop loss of sensation and function.

Symptoms of lumbar spondylosis

Symptoms of lumbar spondylosis follow those associated with each of the various aspects of the disorder: disc herniation, sciatica, spinal stenosis, degenerative spondylolisthesis, and degenerative scoliosis. Pain associated with disc degeneration may be felt locally in the back or at a distance away. This is called referred pain, as the pain is not felt at its site of origin. Lower back arthritis may be felt as pain in the buttock, hips, groin, and thighs. As with spinal stenosis or disc herniation in the lumbar region, it is important to be aware of any bowel or bladder incontinence, or numbness in the perianal area. These signs and symptoms could represent an important massive nerve compression needing surgical intervention (cauda equina syndrome).

Physical Examination

A thorough physical examination reveals much about the patient's health and general fitness. The physical part of the exam includes a review of the patient's medical and family history. Often laboratory tests such as complete blood count and urinalysis are ordered. The physical exam may include:

- Palpation (exam by touch) determines spinal abnormalities, areas of tenderness, and muscle spasm.

- Range of Motion measures the degree to which a patient can perform movement of flexion, extension, lateral bending, and spinal rotation.

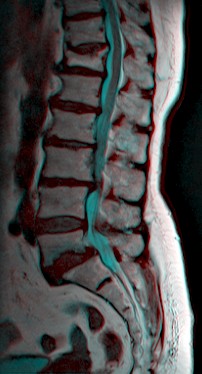

- A neurologic evaluation assesses the patient's symptoms including pain, numbness, paresthesias (e.g. tingling), extremity sensation and motor function, muscle spasm, weakness, and bowel/bladder changes. Particular attention may be given to the extremities. Either a CT Scan or MRI study may be required if there is evidence of neurologic dysfunction.

X-rays and Other Tests

Radiographs (X-rays) may indicate loss of vertebral disc height and the presence of osteophytes, but is not as useful as a CT Scan or MRI. A CT Scan may help reveal bony changes sometimes associated with spondylosis. An MRI is a sensitive imaging tool capable of revealing disc, ligament, and nerve abnormalities. Discography seeks to reproduce the patient's symptoms to identify the anatomical source of pain. Facet blocks work in a similar manner. Both are considered controversial.

The physician compares the patient's symptoms to the findings to formulate a diagnosis and treatment plan. The results from the examination provide a baseline from which the physician can monitor and measure the patient's progress.

Treatment of lumbar spondylosis

Each patient is treated differently for arthritis depending on their individual condition. In the early stages lifestyle modifications or medicines are used for treatment and surgery is needed only if these measures are ineffective.

Some of the ways of Treating Lumbar Spondylosis are:

• Modifying lifestyle including occupational changes if doing manual labor, losing weight and quitting smoking.

• Physical therapy which teaches the patient to strengthen the paravertebral and abdominal muscles which lend support to the spine. General exercises which help build flexibility, increase range of motion and strength.

• A corset or a brace could be used to provide support; cervical collars may be used to alleviate pain by restricting movement.

• Rest combined with anti-inflammatory medications, muscle relaxants and analgesics.

• More powerful anti-inflammatory drugs like corticosteroids can also be injected into the joints to help control pain.

• Hot or cold packs on the affected area, ultrasound and electric stimulation are some of the other treatments which are used.

In more severe cases surgical methods are advised to improve pain and increase motion.

Physical Therapy Management in Lumbar Spondylosis

Goals

- Relief of pain .

- Restoration of movements.

- Strengthening of muscles.

- Education of posture.

- Analysis of precipitating factors to reduce recurrence of the patient's problems.

Management of acute symptoms

- Rest and Support- With acute joint symptoms, a lumbar corset may be helpful to provide rest to inflamed facet joints. When acute symptoms decrease, discontinue corset by gradually increasing the time without the corset. Often the most comfortable position is flexion, esp. if there are neurologic signs due to decrease in the foraminal space from joint swelling or osteophytes.

- Education of posture- Head, neck and shoulders should be supported by the back rest of chair with a small pillow in the lumbar spine, the feet supported and the arm resting on arm rests or on a pillow in the lap.

- Modalities- Hot or cold packs on the affected area, ultrasound and electric stimulation are some of the other treatments which are used to decrease pain and reduce muscle spasm.

- Relaxation- by soft tissue techniques. Teach self relaxation techniques,e.g like deep breathing exercises and physiological relaxation (Laura Mitchell method) and hydrotherapy.

- Traction- Gentle intermittent joint distraction and gliding techniques may inhibit painful muscle responses and provide synovial fluid movement within the joint for healing.

- Gentle ROM within the limits of pain.

Management of subacute and chronic phase

- Increase ROM- Free active exercises of lumbar spine. Pelvic tilting forward, backward in crook lying, quadriped, sitting and standing.

- Mobilization- Restoration of intersegmental mobility by accessory pressure enables the patient to regain full functional painfree movement.

- stretching exercises.

- Strengthening exercises.

- Posture correction.

Return from Lumbar Spondylosis to Orthopedic Physical Therapy

Return from Lumbar Spondylosis

References

- Kirkaldy-Willis WH, Wedge JH, Yong-Hing K, et al. Pathology and pathogenesis of lumbar spondylosis and stenosis. Spine. 1978;3:319–28. doi: 10.1097/00007632-197812000-00004.

- Menkes CJ, Lane NE. Are osteophytes good or bad? Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2004;12(Suppl A):S53–4. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2003.09.003.

- Boos N, Weissbach S, Rohrbach H, et al. Classification of age-related changes in lumbar intervertebral discs: 2002 Volvo Award in basic science. Spine. 2002;27:2631–44.

- Hayden JA, Tulder MW, Malmivaara AV, et al. Meta-analysis: exercise therapy for nonspecific low back pain. Ann Intern Med. 2005;142:765–75.

- Tulder MW, Koes B, Malmivaara Outcome of non-invasive treatment modalities on back pain: an evidence-based review. Eur Spine J. 2006;15(1):S64–81. doi: 10.1007/s00586-005-1048-6.

- Spondylosis. From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia